Broomberg & Chanarin

Spirit is a Bone

Buch

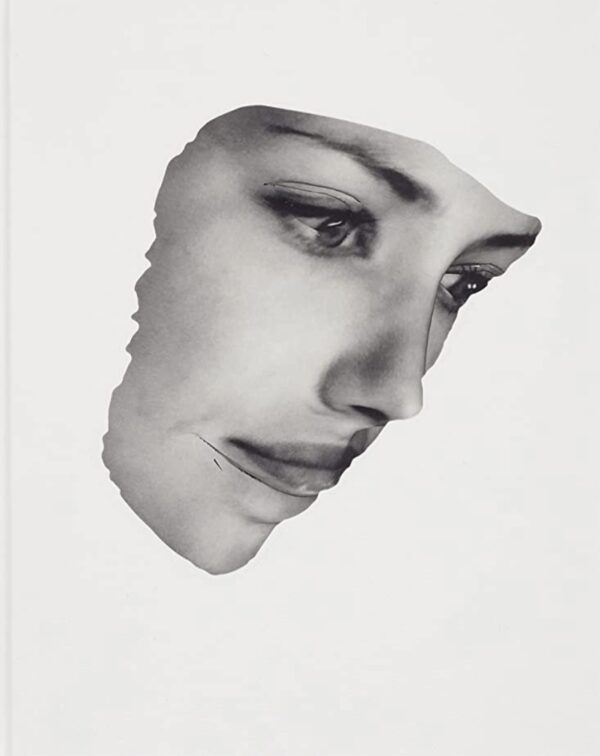

Die Augen leer, das Gesicht so ausdruckslos wie eine Maske: So sehen die Bilder aus, die die beiden Künstler Adam Broomberg und Oliver Chanarin von ihren Protagonisten geschossen haben. Um ihre Porträts zu machen, setzten die zwei Künstler aus London auf dieselbe Gesichtserkennungs-Technologie, die auch in modernen Überwachungssystemen zum Einsatz kommt.

Mithilfe der Technik produzierten Broomberg und Chanarin 120 Aufnahmen von Moskauer Bürgern, die sie zum Teil zufällig auf der Straße angesprochen hatten. Aber auch bekanntere Personen wie die Pussy-Riot-Aktivistin Jekaterina Samuzewitsch oder der Dichter Lew Rubinstein ließen sich für das Projekt mit dem Namen „Spirit is a Bone“ fotografieren.

Mit ihrer Serie greifen die zwei Künstler die anhaltende Debatte um die Überwachung des öffentlichen und auch privaten Raums durch staatliche Behörden und Privatunternehmen auf. Schon jetzt würden Menschen beim Grenzübergang, an Bahnhöfen, Sportstadien und selbst in Kinos erfasst, sagten Broomberg und Oliver Chanarin zum britischen „Guardian“ zu Beginn ihrer Arbeit an dem Projekt.

The series of portraits in this book, which include Pussy Riot member Yekaterina Samutsevic and many other Moscow citizens, were created by a machine: a facial recognition system recently developed in Moscow for public security and border control surveillance. The result is more akin to a digital life mask than a photograph; a three-dimensional facsimile of the face that can be easily rotated and closely scrutinised. What is significant about this camera is that it is designed to make portraits without the co-operation of the subject; four lenses operating in tandem to generate a full frontal image of the face, ostensibly looking directly into the camera, even if the subject himself is unaware of being photographed. The system was designed for facial recognition purposes in crowded areas such as subway stations, railroad stations, stadiums, concert halls or other public areas but also for photographing people who would normally resist being photographed. Indeed any subject encountering this type of camera is rendered passive, because no matter which direction he or she looks, the face is always rendered looking forward and stripped bare of shadows, make-up, disguises or even poise. Co-opting this device, Broomberg & Chanarin have constructed their own taxonomy of portraits in contemporary Russia. Echoing August Sander’s seminal work, Citizens of the Twentieth Century, Broomberg & Chanarin have made a series of portraits cast according to professions. But their portraits are produced with this new technology, with little if any human interaction. They are low resolution and fragmented. The success of these images is determined by how precisely this machine can identify its subject: the characteristics of the nose, the eyes, the chin, and how these three intersect. Nevertheless they cannot help being portraits of individuals, struggling and often failing to negotiate a civil contract with state power. This book is the result of a series of encounters, interactions and conversations between Broomberg & Chanarin and the photography collections at the Library of Birmingham made possible by a commission from GRAIN and the Library with support from the Arts Council of England.